History and Background of Satellite Tracking

These days, we rely heavily on technology. Whether it is for personal, business or scientific use, I think we can all agree that everyday life would be a struggle without it. One important piece of technology that we have utilised at the Rutland Osprey Project over the past few years, is satellite tracking.

Satellite tracking systems enable the monitoring of the routes of migratory and non-migratory birds, which has given us an insight into the birds’ movements. In 1989, a pioneering project studying the Wandering Albatross, used satellite tracking for the first time, which allowed researchers to gain a fantastic understanding of the foraging habits of this species.

Over the past few years, we have fitted adult Ospreys with Argos satellite tags, utilising incredibly lightweight Teflon harnesses. These tags weigh in at around 30g and generate a large amount of information in terms of the birds’ movements. We are able to learn more about foraging habits for individual bird’s, both at their wintering grounds and throughout the breeding season. With satellite tracking data transmitted almost every hour, it allowed us to follow the exact route they took during their migrations. We were even able to pinpoint the exact tree they perched in overnight.

With the exception of 30(05), the other Ospreys that were fitted with satellite tags have been male, including S1(15) and 4K(13). Males were the preferred choice since they are the most active throughout the year, particularly during the breeding season. They will spend a lot of their time roaming around during fishing trips, intruding at other nest sites and chasing invading Ospreys away. This is also coupled with the fact that males will start to hold territories at sites as they become older, and therefore are theoretically easier to catch and fit with a tag.

With female Ospreys being more likely to settle down with a mate and breed at a younger age, much of the information we were likely to receive came from their migratory routes. Juveniles tend not to be fitted with tags, although it would be interesting to compare their first migratory route with future migrations. Another consideration is that unfortunately juveniles have a high mortality rate, with only 30% of juvenile Ospreys expected to return and with satellite tags costing approximately £2000 each, it makes better financial sense to fit them to adult birds.

So why was 30(05) fitted with a tracker if she is female? In 2013, when attempts were being made to catch birds for satellite tracking under the help and guidance of Roy Dennis, it took 48 hours of trying before 30(05) was accidentally caught. Back then she was a non-breeder, having lost her partner the year prior and, since they had two satellite tags and had already caught an Osprey, it was decided to fit her with one. Unfortunately, 30(05)’s tag stopped working during the 2019 breeding season, so we are no longer able to track her on migration, but we have learnt a lot from her, in particular that she can travel very fast during her migrations. One year it took 30(05) only 12 days to fly nearly 3000 miles between Rutland and her wintering spot in Senegal.

Over the years, we have learnt a lot about Ospreys’ migratory routes, where they fish and where they spend their winter months. We now understand that Ospreys are creatures of habit and will follow the same routes for their migrations year after year, sometimes visiting the same feeding spots and even perching on the same trees overnight. We also know now that they are not only site faithful to their breeding grounds, usually the same area they fledged, but will also return to the same beaches and fishing spots in their wintering grounds. Some individuals will travel far and wide throughout the summer and some will stay within one particular area, whether it is for foraging purposes or otherwise. What we can say is that each bird is an individual and has its own preferences for travel, foraging and more.

Spring Migration 2020

The two satellite tagged male Ospreys S1(15) and 4K(13), returned to Rutland after wintering in Guinea-Bissau and Guinea respectively. S1 left Guinea-Bissau on 8th March and arrived back in Rutland 28 days later on 4th April. 4K was slightly later starting his migration and left the coast of Guinea on 27th March and arrived back in Rutland on 13th April, after 18 days of travel.

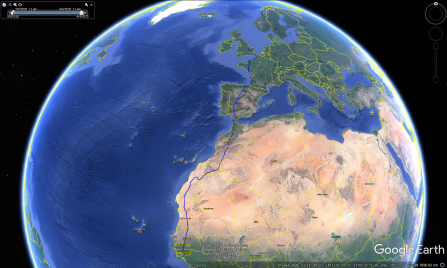

4K(13)’s full migratory route Spring 2020

S1(15)’s full migratory route Spring 2020

S1(15)’s and 4K(13)’s full migratory routes for Spring 2020

(S1’s route is in blue and 4K’s is in red)

To download the images, follow the links below:

4K(13)'s full migratory route Spring 2020

Autumn Migration 2020

Having lost male, S1(15), earlier in the season, male 4K(13) was the last Osprey within the Rutland population fitted with a satellite tracker. 4K(13) spent the winter months in Guinea, around 6,700km away, left Rutland on 14 September and arrived in Guinea 30 days later on 13 October.

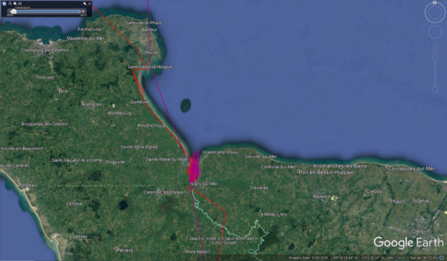

After arriving in the north of France on 15 September, he spent the following ten days fishing within the area before continuing his journey south. Unlike the need to return promptly to the breeding grounds during the spring migration, the autumn migration for Ospreys can be much slower as there isn’t so much of a rush to reach their wintering grounds.

The below image is the full route 4K(13) took on his autumn migration this year.

To download 4K(13)'s full autumn migration follow the link below.

Spring Migration 2021

4K(13) left his wintering grounds on 21st March 2021 and spent 25 days travelling back to the Rutland area, where he arrived on 14th April. On his migration, he made a long sea crossing between Morocco and Portugal, which could have been a result of some adverse wind conditions. After arriving in southern Portugal, he spent several days there resting before starting his migration again.

To view and download 4K's full spring migration please follow the link below.

Autumn Migration 2021

The satellite tracked male, 4K(13), left Rutland on 31st August and spent 24 days on migration to Guinea, where he arrived on 23rd September. His average speed on this particular migration was 23kph, but his top speed was and incredible 40kph! On average, 4K(13) flew at an altitude of 89m above sea level, however he reached 311m when he crossed the Atlas Mountains.

It was really interesting to see that, like the previous year's autumn migration, 4K(13) spent a few days fishing at what must be a good fishing spot in the north of France (see image below).

To view and download 4K(13)'s full autumn migration this season please follow the link below.